Creating CTI Like a Journalist

Key Takeaways

- Treating CTI like journalism helps ensure investigations remain objective, well-documented, and focused on facts rather than assumptions.

- A journalistic mindset encourages thorough sourcing, careful verification, and clear attribution - critical when sharing intelligence with others.

- Story-driven intelligence reports are easier to understand, communicate, and act on, especially for stakeholders outside the security team.

- Structuring CTI output like an article helps create audit trails, supports collaboration, and improves long-term analysis quality.

- Analysts using journalistic discipline turn scattered data into coherent intelligence that can drive detection, response and risk decisions effectively.

I have a feeling that for a lot of cybersecurity people, cyber threat intelligence (CTI) has a nebulous quality. They kind of know what it is, but can’t clearly define it.

Here’s the one-sentence definition of organisational CTI I like to use:

Your threat intel team are the eyes and ears of your organisation, arming decision makers with the intelligence they need to make better decisions.

The mission of a CTI team is to produce relevant intelligence and deliver it to decision-makers in an actionable form.

We use tech to enable this process, but for many CTI analysts, tech is our comfort zone and can easily become our primary focus: TIPs, STIX, TAXII, MISP, IoAs, IoBs, IoCs, TLPs… the list could go on.

I'm going to argue that as CTI analysts, we often get lost in the middle of these technical woods and forget about the ultimate purpose of threat intel: our outputs.

These are commonly called threat intelligence products; the reports, alerts, or briefings we send to help others make decisions and take action.

So how do we stay focused on the real purpose of CTI: producing useful, actionable outputs? Consider the lessons from an occupation we’ve had lifelong exposure to: journalism.

Let’s put on our journalistic hats for a second.

Imagine there’s significant flooding happening in our city. Different media outlets would have different takes on this depending on their audiences.

- A local newspaper would report which suburbs are affected and where to find emergency resources.

- An insurance industry magazine might analyse the long-term impact on premiums.

- A newspaper on the other side of the world might ignore it entirely.

CTI teams should adopt a similar mindset. We need to understand our audience, what they care about and how they’ll use our intelligence, so we can produce outputs that are useful and relevant to them.

Let's go back to primary school: the 5W + H

When you were in primary school (or elementary school in the US), chances are your teacher taught you the basics of how to write a newspaper article. And chances are, they introduced you to a golden rule: cover who, what, when, where, why, and how, or the 5W + H.

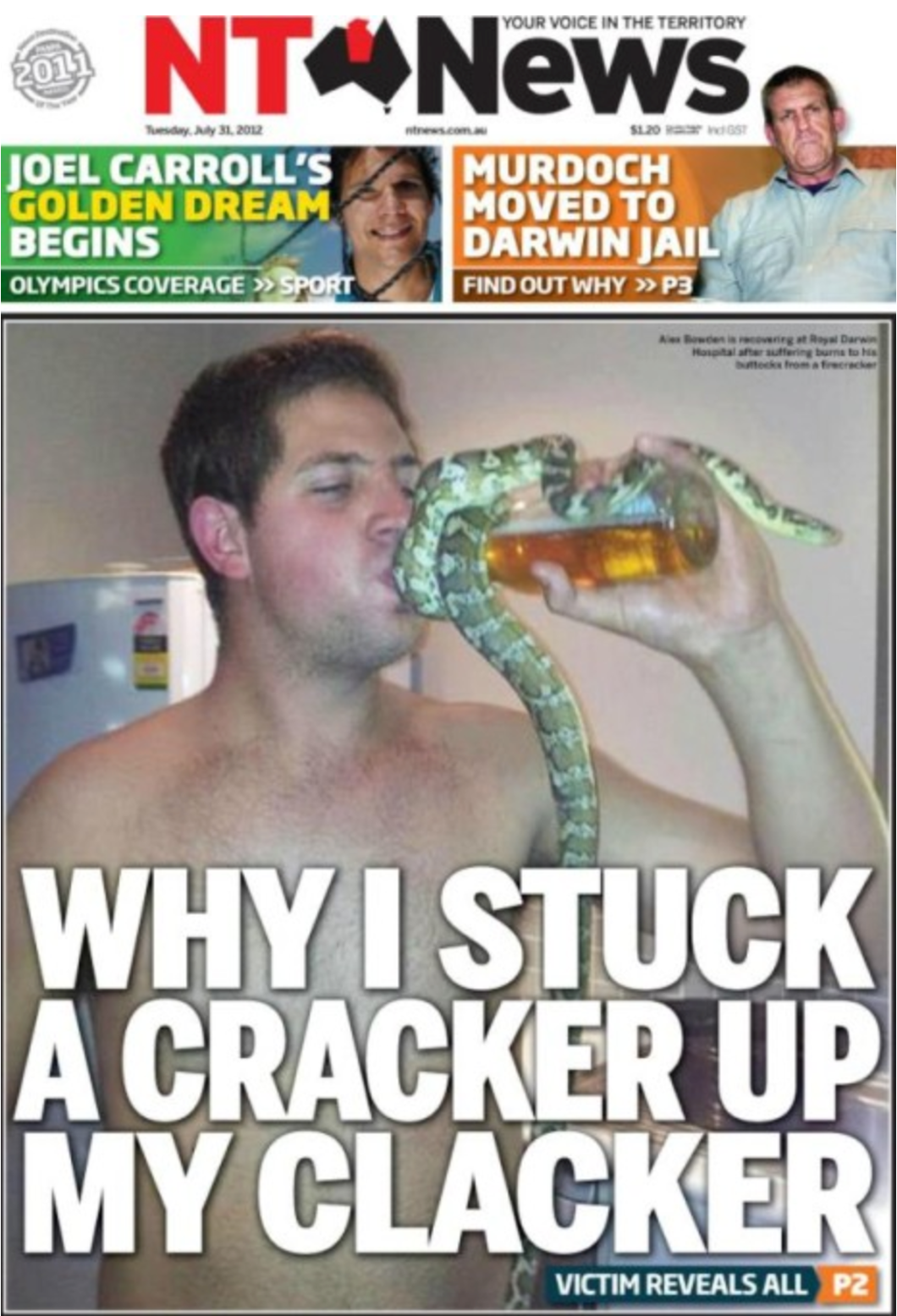

Here’s a Walkley Award-winning example (seriously) from the NT News that demonstrates how effectively 5W + H can be packed into a few lines:

An extract of the accompanying article:

A MAN who suffered serious burns when friends lit a firecracker in his bum says he was just showing his visiting mates a Territory good time.

Alex Bowden, 23, of Wagaman, Darwin, put a spinning “flying bee” winged firework in his butt crack during a party at a rented house on Rossiter St, Rapid Creek on Saturday night.

“I had a few lads up from Queensland and I had to put on a good show,” he told the NT News from his hospital bed.

“I just had a few beers with the boys and let off a few firecrackers.

“And I put one in my arse.”

Here's how it stacks up against the 5W + H model:

Who? The guy with the bottle of beer and a snake wrapped around it.

What? He got burned.

When? Last Saturday night.

Where? Rapid Creek.

Why? He was drunk with a couple of mates.

How? The headline famously explains that one.

In journalism, the point of 5W + H is to get key facts to the reader quickly, especially if they only skim the first two paragraphs.

The same principle applies to CTI reports, like briefings or analysis documents. One mistake many of these reports make is “burying the lede”, a journalistic sin where the whole point of the story is buried way down in the details of paragraph six.

Going beyond “what”

Collectively, CTI analysts tend to focus on the technical aspects of a threat: hashes, IPs, C2 domains, MITRE ATT&CK IDs and file paths. Some threat intel “reports” just look like this:

192.168.45.67

172.16.89.101

203.0.113.215

10.255.12.34

198.51.100.98

66.249.79.12

8.8.4.4

This is the “what” missing the other 4 W + H; that is to say, it’s lacking context.

Although we often have amazing providers of external threat intelligence, the job of our internal team is to translate this external reporting into verified intelligence recast through our organisation's lens. This is something only an internal team can do well. We could call this recontexualisation to the unique aspects of our organisation.

How fast do we have to move?

What can we do?

What could the impact be?

If we do nothing about this threat, what will happen?

How would the threat actor carry it out?

What should we do in response?

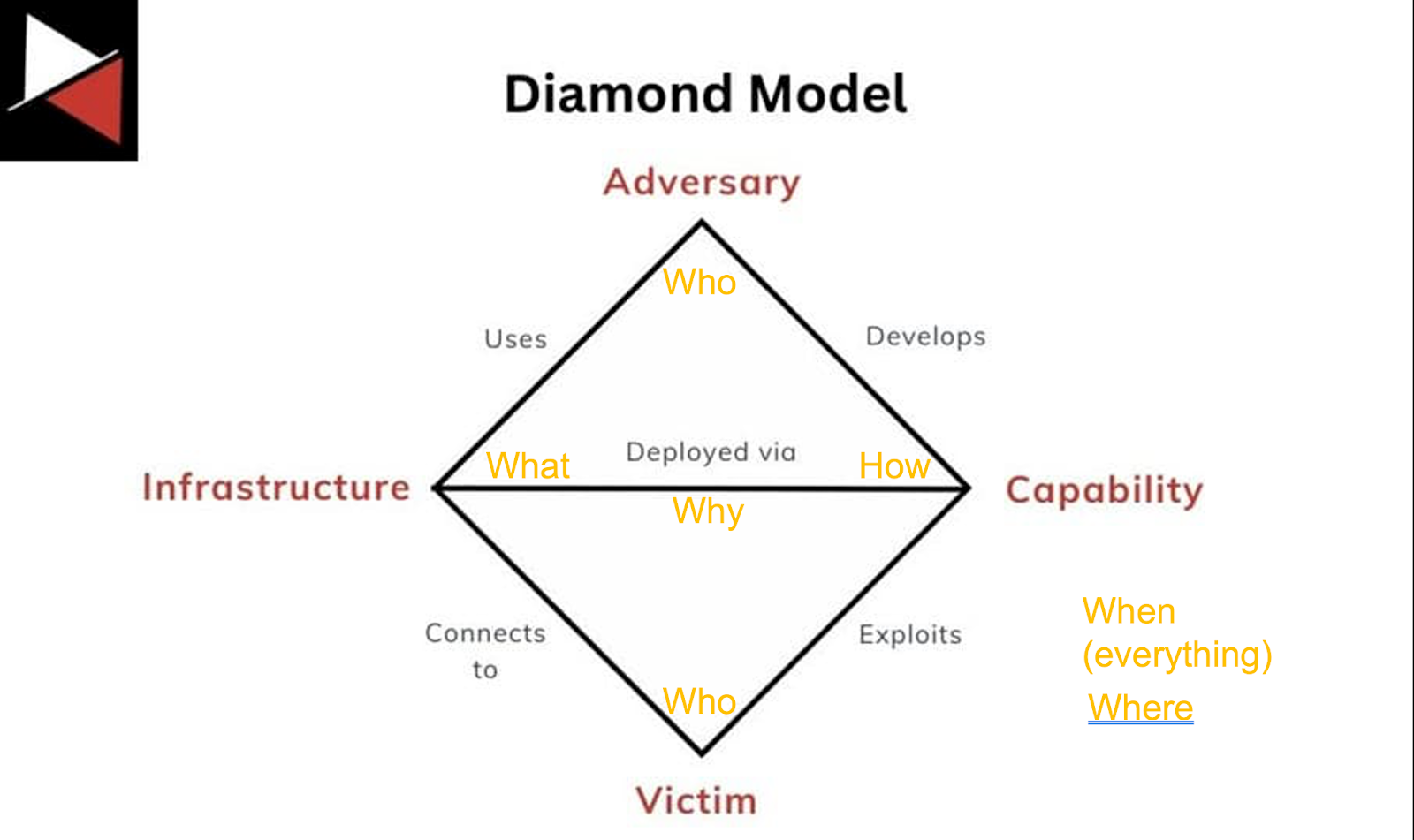

These questions come up so often that the CTI field has its own version of 5W + H, the Diamond Model. Here's how it roughly maps:

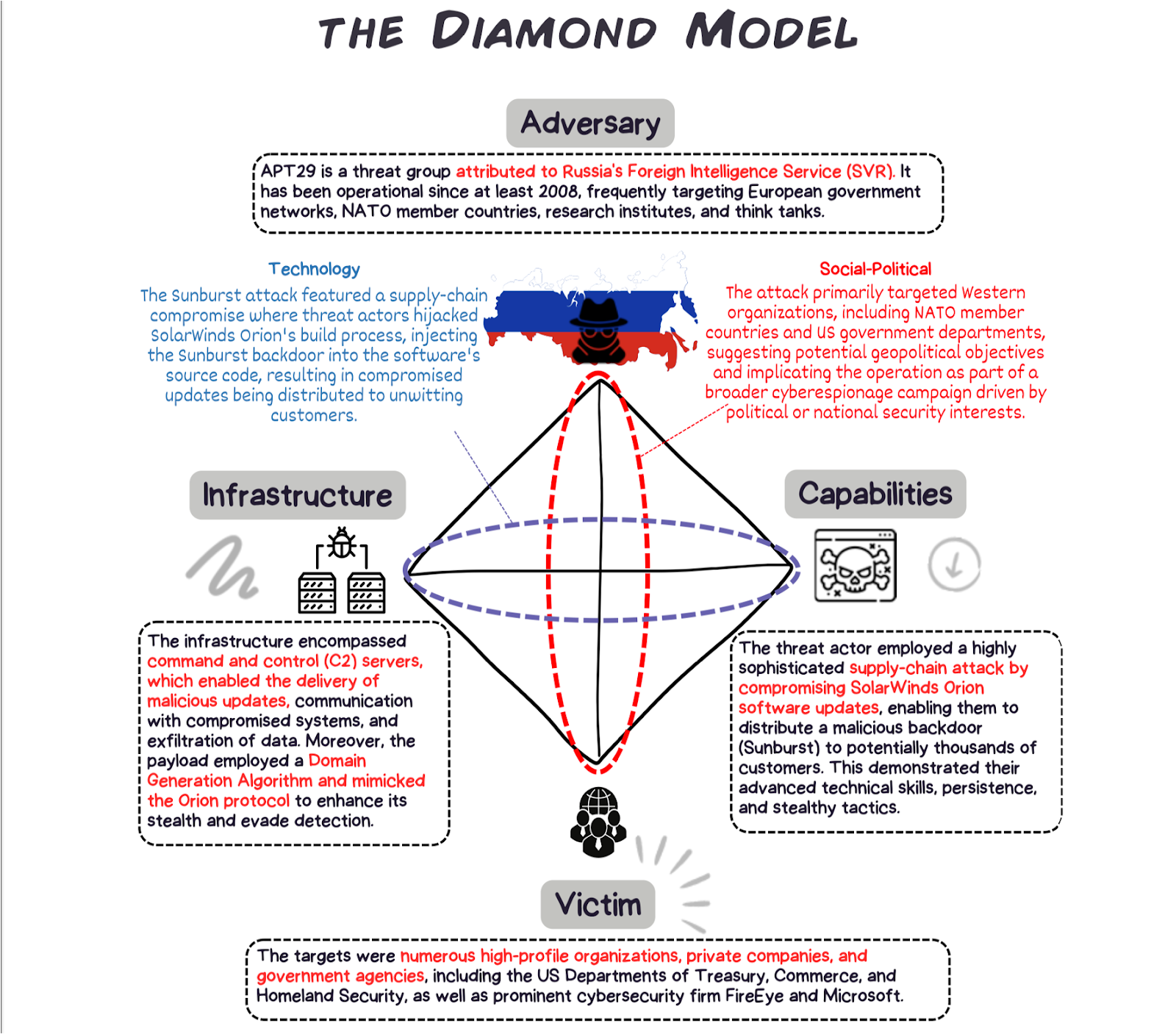

As an example, here’s how the diamond model can be applied to one of the biggest cyber security incidents of the last decade, the Solarwinds supply chain hack:

Weighing sources

We can sometimes think about the threat intelligence reports we read as containing facts, when we should instead think about them as containing opinions.

Someone’s claiming X, but who is saying that?

How would they know?

What was their methodology?

Who else is saying that?

Can we confirm it ourselves?

In journalism, it’s considered poor practice to rely on a single source. Instead, good journalists gather information from multiple sources. This allows them to verify that what they’re publishing is credible information.

Let’s dig into how we might apply a similar standard to the threat threat intelligence we produce:

The source of sources

Where do our respective fields get intelligence from?

We often call using publicly shared content and doing lookups and enrichment “open source intelligence”, aka OSINT. Note that while this is called “intelligence” it must be verified and cross-checked!

Weighting intelligence

If you were a journalist, you might get a lead from the BBC or from a random post on Reddit. Both could point to a real story, but the difference is in how much scrutiny the information has already gone through. The BBC operates under a defined editorial process, with rigorous standards for verification and accountability. In contrast, any person or bot can post on Reddit with virtually no oversight.

We’d say that in contrast to the Reddit post, the BBC is a reliable source with a known methodology, and that anything it publishes meets a minimum standard of confidence, typically backed by multiple sources (most of the time).

The same applies in threat intelligence. Because we often deal with unverified information and analyst interpretation, not concrete facts, we need clear ways to distinguish between well-researched intelligence and speculative claims.

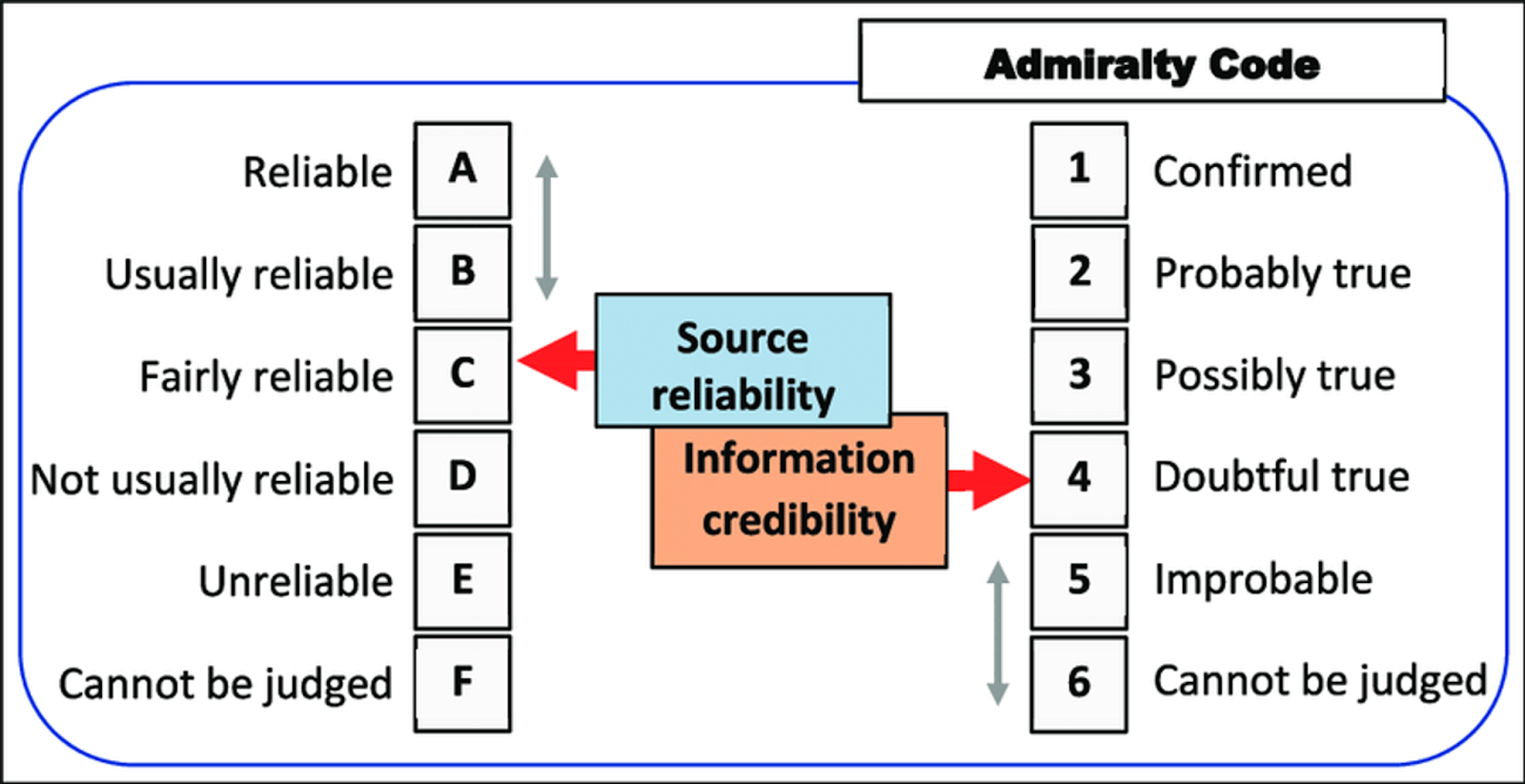

In intelligence, we already have an established system for evaluating the reliability of sources and the credibility of their information: the Admiralty Code (also known as the NATO source reliability and information credibility rating system). It was originally developed by naval intelligence and is still widely used across intelligence disciplines.

The Admiralty Code uses a two-part scale:

- One letter (A - F) to rate the reliability of the source, based on past performance.

- One number (1 - 6) to rate the credibility of the information itself, based on how well it’s corroborated.

We might rate the reliability of the BBC as an A (proven history of reliability), whereas our random internet denizen is an F (their reliability cannot be judged). The specific information the BBC published might be a 1 for credibility if we can cross-check it (Confirmed), whereas our random Reddit comment, intriguing as it might be, is likely a 6 in isolation (credibility cannot be judged). We can combine these codes to form an A1, an F6, or anything in between.

Journalists follow well-established norms, but there’s no formal system like the Admiralty Code. It’s one of the few areas where our field has a codified standard and journalism doesn’t.

An Admiralty Code rating can be included in threat intelligence reports to succinctly indicate the reliability and credibility of the information. The popular open-source threat intelligence platform MISP also includes an Admiralty Scale taxonomy, enabling analysts to attach admiralty codes to MISP events.

Analysis

Journalists don’t just list all the isolated facts and information snippets they receive. They assemble them into a verified, coherent story to provide insight.

A lot of the “intelligence” reports we see in cyber security don’t have this same rigour - they’re often just a list of indicators of compromise with no context, e.g. a tweet which says “here’s a list of bad hashes: [20 hashes follow]”.

Often when we share information about threats we’re pasting URLs into Slack or retweeting a report with no additional commentary adding valuable context for the threat to our organisation. While this is certainly threat information, it's the value we add through analysis and recommendation that turns what we share into intelligence.

Here in Australia, we have a show called Media Watch which publicly calls out media outlets to critique dishonesty and poor fact checking and analysis.

Journalism is a discipline that has existed for hundreds of years and has had ample time to develop professional standards (although, as you’ll know, they are frequently deviated from!). When those standards aren’t met, media outlets are expected to publish retractions and correct the record. If not, they might find themselves on Media Watch.

While military intelligence has existed for thousands of years, cyber threat intelligence is still in its infancy. Standards and practices are only beginning to be developed and debated, although the best practitioners do an excellent job at their craft.

As CTI practitioners, we can reflect on the rigor that reputable media outlets strive for and incorporate the best practices we observe, particularly in ensuring accuracy and context, into our intelligence reporting.

For us, the consequences of inaccuracy aren’t being roasted on national TV, but they’re still significant: we lose trust. Once decision-makers dismiss our reports as unreliable, it’s hard to get that trust (and attention) back.

Analysis alone is not enough - we need to produce

For journalists, writing isn’t enough. Their work needs to be read, and read widely, to be considered successful. In the world of online news, media outlets track detailed analytics on what readers click and engage with. Output and attention are the king and queen of journalistic performance.

Although there are downsides (high-volume news cycles and clickbait, anyone?) output and attention are equally useful aims for us as CTI analysts. I’ve certainly seen CTI teams who are so caught up in collecting, processing, and analysing incoming intelligence feeds that they forget to produce, the whole point of the endeavour!

Intelligence products

Those things we produce from our dedicated intelligence cycle work are called intelligence products. Two classic examples would be intelligence reports for humans, and intelligence feeds for security controls like firewalls.

One thing that some CTI teams miss is defining exactly what’s on their “menu” of intelligence products.

Who are we producing for?

What is their role?

What do they need from us to make decisions?

How do they prefer to consume information?

Once we know what we’re producing, and who it’s for, we’ll have a much clearer view of how the rest of the intelligence production cycle should support that. Start with the output, and work backwards.

Tone and terminology - know your audience

A journalist friend who worked for a suburban newspaper once told me “we assume our audience has a reading age of 10 and we write accordingly”. This is also the valuable lesson of knowing your audience.

As highly technical analysts, we like to show all the painstaking research that went into supporting our conclusions. And yet busy executives and technology platform owners rarely have the time or security background needed to make sense of all that technical analysis. What they really want to know is: so what do I do? How do I factor what you’ve found into my decision making?

We need to translate our necessary technical analysis into language that ensures our recipient won’t get overwhelmed or miss the “so what” of our reporting. Our job is to write clearly, simply, and concisely so they understand the point we’re getting across, and the course of action we’re recommending in response.

Relevance, accuracy, timeliness, actionability, contextual relevance

Good threat intelligence, just like good journalism, is:

- Relevant

- Accurate

- Timely

- Actionable

- Contextual

Similarly, a suburban Australian newspaper isn’t going to run a front-page story on fluctuations in the Peruvian peso. Not because it isn’t interesting, but because it isn’t relevant to their audience.

Just because something is technically interesting or circulating in threat feeds doesn’t mean it needs to be forwarded internally. CTI’s role is to act as a focusing lens for the organisation. That means being ruthless about what matters to your stakeholders and discarding what doesn’t. Relevancy is determined by who your audience is and what decisions they need to make.

Timeliness matters too. In journalism, there’s an old saying: today's news is tomorrow’s fish and chip wrapper. The same is true in CTI. If we take too long to process and contextualise intelligence, it may no longer be relevant by the time we share it. If we want to help our organisation make better decisions, we have to deliver insight while it’s still fresh enough to act on.

Information that's still fresh enough to act on is much more likely to be actionable.

Good CTI doesn’t just describe a threat, it recommends what to do about it. This is where we can actually go one better than journalism. Most news stories can’t offer the reader any practical response (e.g. climate change articles that conclude with “turn off your lights”), but in CTI, we can and should suggest next steps. If we’re raising an issue with stakeholders, we should also explain what response options they have, what level of urgency is required, and what the trade-offs might be between different courses of action.

Put simply: if I tell stakeholders this, what are they likely going to do with the information? And if I don’t know, why am I sharing it?

Less volume, more relevance

Relevance must always come before volume. Stakeholders will quickly start ignoring us if we send them everything we see. If everything is important, then nothing is important.

This reminds me of John Stewart’s (former host of The Daily Show) criticism of the 24 hour news cycle:

24-hour news networks are built for one thing, and that's 9/11 and that type of gigantic news event. The type of apparatus that exists in this building and in the other 24-hour news channels is perfectly suited to cover that.

In the absence of that, they're not just going to say, "There's not that much that's urgent or important or conflicted happening today," so they are going to gin up—they are going to bring forth—more conflict and more sensationalism, because they want you to continue watching them 24 hours a day, seven days a week, even when the news doesn't necessarily warrant that type of behavior.

Although output and attention are important in CTI, we don’t want to run our CTI program like a 24 hour news cycle. Some teams set output goals like “publish 10 intelligence reports per week”, but relevance typically drops as output pressure increases. It’s far better to share one well-curated, high-context insight than overwhelm recipients with low-signal noise.

The bottom line

Cyber threat intelligence is not about tools or feeds; instead, it’s a communication function.

Like journalism, our job is to gather, interpret, and deliver information. That means we have to understand our audience, present intelligence with clarity and context, and focus on outcomes over activity.

Journalists use the 5W + H to structure their stories. We use the Diamond Model.

Journalists vet and verify facts based on multiple sources and who is saying it. We use the Admiralty Code with confidence and relevance.

Journalists always think about their audience and measure their engagement to understand what they’re interested in and how they consume information. As CTI analysts, so should we.

And just like the best journalism, the best CTI is timely, accurate, and above all, actionable.

But there’s one place where we can go further than news journalism: we can recommend a course of action for the reader. We can influence decisions directly and ultimately, influence outcomes.

This only works if we resist the pressure to fill airspace. The 24-hour news cycle creates noise for the sake of it. Good CTI should reduce noise and focus attention.

So next time you’re writing a one-pager for the SOC or your execs, ask yourself:

- What's the "So what?" What's the bottom line for the stakeholder?

- Is this highly relevant to our organisation?

- Is it timely enough for us to act on?

- Have I made it clear what they can or should do in response?

If you can answer yes to all four, congratulations: you’re not just doing threat intelligence. You’re doing it well.